Curatorial Projects

Curatorial Projects

Somerville Museum Somerville, MA January – March, 2022

Another Space Gallery Co-Curated with Estrellita Brodsky Second version of show presented for the 10th Edition of Untitled Art Fair (Miami Beach, 2021) New York, NY Feb – May, 2022

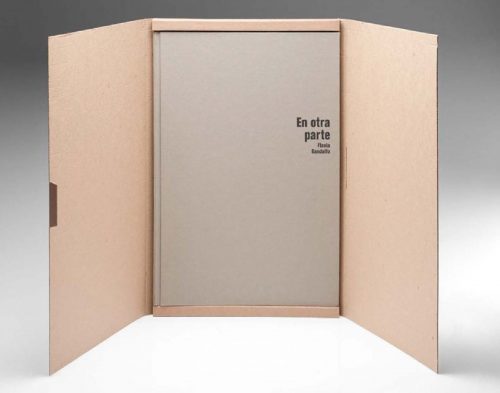

by Ximena Garrido-Lecca and Ishmael Randall Weeks

Curator, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Lima (Mac)

Lima, Perú

October 2019 – March 2020

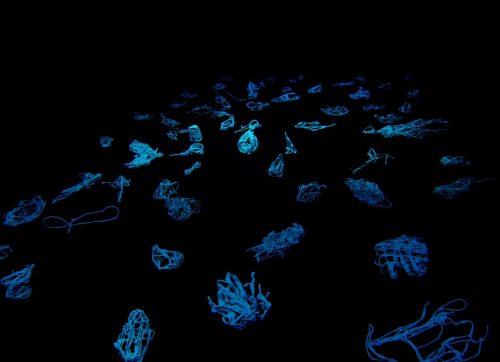

Curator LIFEWTR Launching Exhibition, Casa Orizaba, Gallery Weekend Mexico City, Mexico September 2018

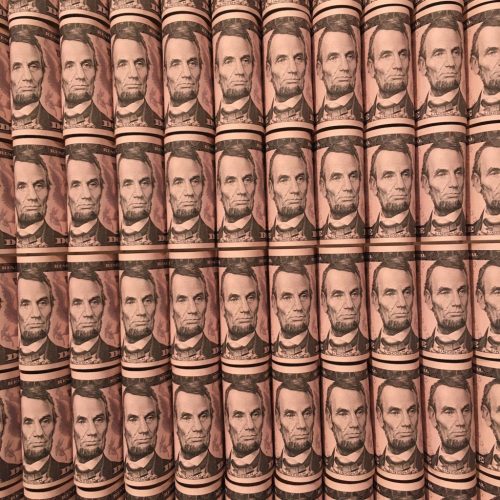

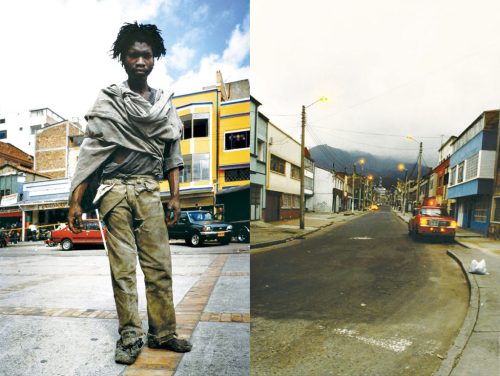

by Santiago Montoya Curator, Espacio El Dorado Bogotá, Colombia

Curator Art Museum of the Americas. Washington, D.C. October 2016-April 2017

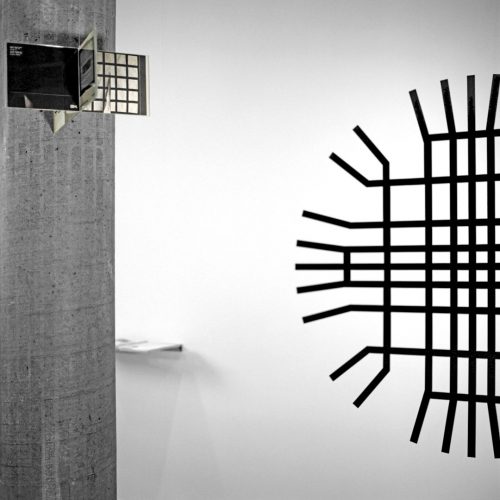

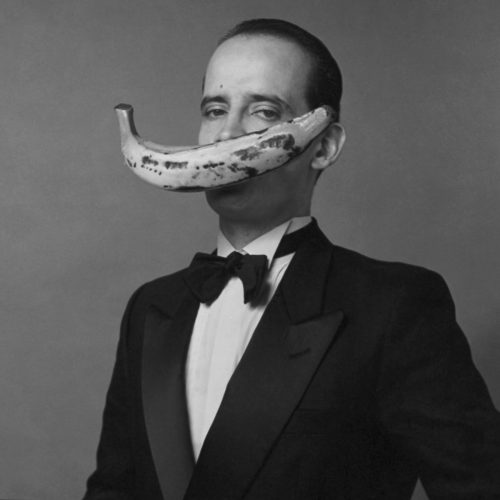

by Augusto Ballardo

Curator, Galería Impakto

Lima, Perú

October 2016

Curator, Galería Enlace

Lima, Perú

June-July 2011

Curator, Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts and David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University Cambridge, MA March-April 2011

Curator David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University

and Museo Nacional de Colombia

Bogotá, Colombia

February 23-May 24, 2011

Curator, A Selection from the Permanent Collection of the David Rockefeller Center Mills Gallery - Boston Center for the Arts Boston, MA May-June 2010

Curator, Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts and David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University Cambridge, MA February-March 2010

Curator, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University, Presented at Pinta Art Fair New York, NY November 2009

Curator, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University Cambridge, MA February-May 2008

Co-Curator, Americas Society New York City, NY April-August 2007

Curator, The Americas Society New York, NY February, 2007-May 5, 2007

Curator, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University Cambridge, MA October-November 2007

Curator, Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts and David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University Cambridge, MA October 26, 2006-January 5, 2007

Curator, CGIS -David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University Cambridge, MA September 28, 2006-June 30, 2007

Curator, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University Cambridge, MA March 8-June 1, 2006

Curator, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University Cambridge, MA February 17-April 8, 2005

Curator, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University Cambridge, MA September 30, 2004-January 05, 2005

Curator, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University Cambridge, MA February 18-June 30, 2004

Curator, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University Cambridge, MA September 25, 2003-January 15, 2004

Curator, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University Cambridge, MA February 21-August 30, 2003

Curator, David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard University. Cambridge, MA September 26, 2002-January 15, 2003